Last week I re-read The Three Body Problem, a wonderful work of science fiction that blends the madness of China’s Cultural Revolution, itself just another iteration of civilizational madness, and asks the question: how should we respond to alien first contact?

The author’s afterword captures why so many people are inspired by science fiction.

I’ve always felt that the greatest and most beautiful stories in the history of humanity were not sung by wandering bards or written by playwrights and novelists, but told by science. The stories of science are far more magnificent, grand, involved, profound, thrilling, strange, terrifying, mysterious, and even emotional, compared to the stories told by literature. Only, these wonderful stories are locked in cold equations that most do not know how to read.

The creation myths of the various peoples and religions of the world pale when compared to the glory of the big bang. The three-billion-year history of life’s evolution from self-reproducing molecules to civilization contains twists and romances that cannot be matched by any myth or epic. There is also the poetic vision of space and time in relativity, the weird subatomic world of quantum mechanics … these wondrous stories of science all possess an irresistible attraction. Through the medium of science fiction, I seek only to create my own worlds using the power of imagination, and to make known the poetry of Nature in those worlds, to tell the romantic legends that have unfolded between Man and Universe.

It reminded me of the time 11 years ago when I did a seven-day survival course in Utah’s high desert. I was terrible at the survival part — don’t look to me for help when there’s a zombie apocalypse — and I was kind of meh on the whole “majesty of nature” thing that many others get from the wilderness.

However, on the last night I had an epiphany. We had to walk individually in the dark for an unknown distance (“just walk until you see the campfire”) that ended up being about 10 miles. There was no moon. The air was clear, and our location one of the most remote places in the lower 48, so there was incredible depth and clarity of all the stars in the sky. I thought of how humans have been looking up at the stars for hundreds of thousands of years, perhaps millions, and trying to make sense of them.

It’s one thing to look at pretty lights in the sky. It’s another to know that those lights come from stars that are millions of light years away.

In the distant past, humans had practically no knowledge about the stars, or exercise, or nutrition or germs. But we wanted to know, so we made up stories to explain things. Gods, spirits, UFOs, “the ether” – all of these are attempts to explain the unknown. Most hypotheses have been discredited, and many more will be. Nonetheless, there is something beautiful about the desire to know and how knowledge impacts our ability to feel a sense of awe about the universe.

The scale of the universe is far more awe-inspiring than the simple tales we’ve told ourselves in the last few thousand years. And it’s not just the scale of inert objects. The depth of human consciousness, the fundamental weirdness of quantum physics… no matter the zoom level we choose, there is mystery, awe... and even more knowledge to be won.

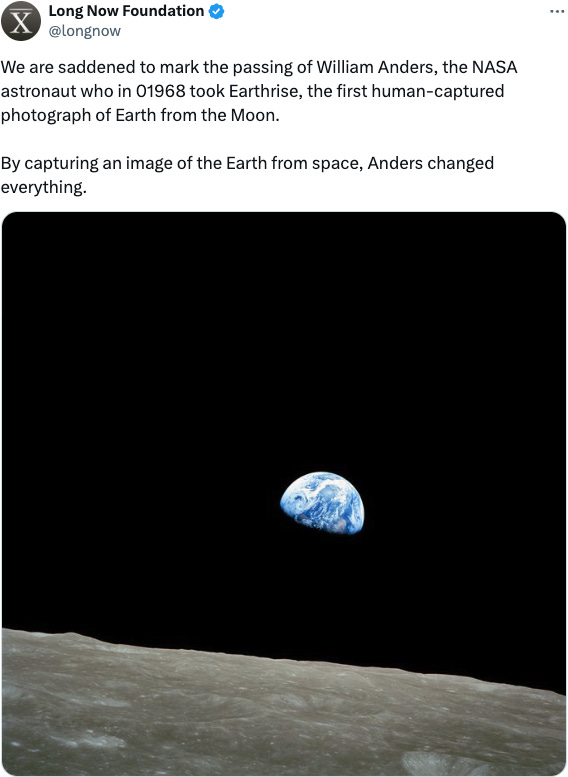

Two days ago the astronaut William Anders died in an aviation accident. I never knew his name until I saw the tweet below. What a watershed moment this was in the history of human consciousness — a miracle of science that shows what’s possible even amidst the chaos and suffering of 1968.

What bothers me is the simplicity of the human values in the old myths...